How Did Descartes Explain How The Brain Controlled Movement?

The pineal gland is a tiny organ in the center of the brain that played an important role in Descartes' philosophy. He regarded information technology every bit the chief seat of the soul and the identify in which all our thoughts are formed. In this entry, we hash out Descartes' views apropos the pineal gland. Nosotros likewise put them into a historical context by describing the master theories almost the functions of the pineal gland that were proposed before and after his fourth dimension.

1. Pre-Cartesian Views on the Pineal Gland

The pineal gland or pineal body is a small gland in the centre of the head. It often contains calcifications ("brain sand") which make it an easily identifiable point of reference in X-ray images of the encephalon. The pineal gland is attached to the outside of the substance of the brain near the archway of the canal ("aqueduct of Sylvius") from the third to the quaternary ventricle of the encephalon.

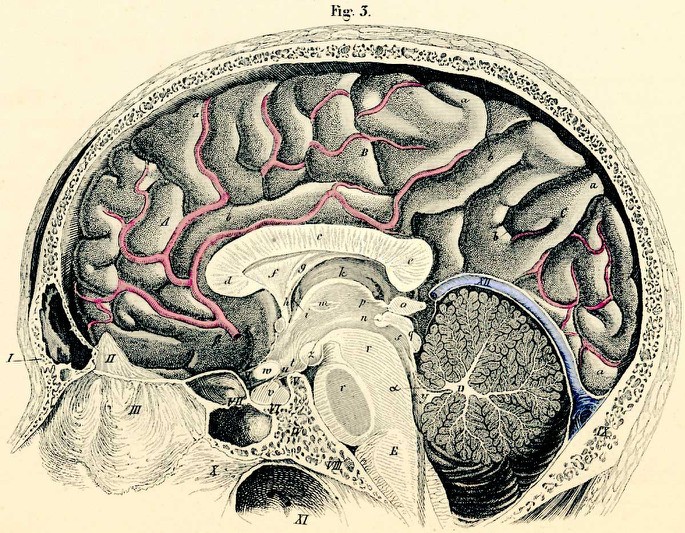

Figure one. The Pineal Gland. Sagittal department of brain, view from the left, the surface of the medial half of the right side is seen. Source: Professor Dr. Carl Ernest Bock, Handbuch der Anatomie des Menschen, Leipzig 1841. From a scan originally published at: Anatomy Atlases (edited). Figure labels are as follows:

(I) Frontal bone (with frontal sinus); (Two) Crista galli (of ethmoidal os); (III) Perpendicular lamina of the ethmoid bone; (Iv) Trunk of the ethmoid bone; (V) Back of the sella turcica (posterior clinoid process); (VI) Sella turcica; (Seven) Sphenoid sinus; (Viii) Basilar office of the occipital bone (with the fossa for medulla oblongata); (IX) Occipital part of the occipital os; (X) Vomer; (XI) Pharynx; (XII) Tentorium cerebelli (with confluence of sinuses and opened great cerebral vein of Galen).

(A) Anterior (Frontal) cerebral lobe; (B) Centre (Parietal) cognitive lobe; (C) Posterior (Parietal) cerebral lobe; (D) Medulla oblongata.

(a) gyri; (b) sulci (furrow between gyri); (c) corpus callosum (body); (d) genu of corpus callosum; (e) corpus callosum, splenium; (f) septum pellucidum; (g) fornix (body); (h) fornix column; (i) foramen of Munro; (chiliad) thalamus (optic thalamus); (l) anterior commissure; (one thousand) interthalamic adhesion; (n) posterior commissure; (o) pineal gland; (p) stem of pineal gland (crus glandulae pinealis); (q) corpora quadrigemina; (r) pons Varoli; (s) aqueduct of Sylvius; (t) tuber cinereum; (u) infundibulum; (five) pituitary gland (hypophysis); (w) optic chiasm; (x) optic nerve; (y) fourth ventricle; (z) mamillary body.

(α) anterior cerebellar valvule; (β) anterior cognitive avenue;

It is nowadays known that the pineal gland is an endocrine organ, which produces the hormone melatonin in amounts which vary with the time of day. But this is a relatively recent discovery. Long before information technology was fabricated, physicians and philosophers were already busily speculating about its functions.

i.ane Antiquity

The first clarification of the pineal gland and the first speculations about its functions are to be found in the voluminous writings of Galen (ca. 130-ca. 210 CE), the Greek medical doc and philosopher who spent the greatest part of his life in Rome and whose arrangement dominated medical thinking until the seventeenth century.

Galen discussed the pineal gland in the eighth book of his anatomical work On the usefulness of the parts of the trunk. He explained that information technology owes its proper name (Greek: kônarion, Latin: glandula pinealis) to its resemblance in shape and size to the nuts found in the cones of the rock pine (Greek: kônos, Latin: pinus pinea). He called information technology a gland considering of its appearance and said that it has the aforementioned function every bit all other glands of the body, namely to serve as a support for blood vessels.

In order to sympathize the rest of Galen'southward exposition, the following two points should be kept in mind. First, his terminology was different from ours. He regarded the lateral ventricles of the brain equally one paired ventricle and chosen it the anterior ventricle. He appropriately chosen the third ventricle the middle ventricle, and the 4th the posterior one. Second, he thought that these ventricles were filled with "psychic pneuma," a fine, volatile, airy or vaporous substance which he described as "the first instrument of the soul." (See Rocca 2003 for a detailed description of Galen's views about the beefcake and physiology of the brain.)

Galen went to great lengths to refute a view that was plainly circulating in his fourth dimension (simply whose originators or protagonists he did not mention) co-ordinate to which the pineal gland regulates the flow of psychic pneuma in the canal between the middle and posterior ventricles of the brain, just equally the pylorus regulates the passage of nutrient from the esophagus to the tum. Galen rejected this view because, commencement, the pineal gland is attached to the outside of the brain and, second, it cannot move on its own. He argued that the "worm-like appendage" [epiphysis or apophysis] of the cerebellum (nowadays known as the vermis superior cerebelli) is much better qualified to play this role (Kühn 1822, pp. 674–683; May 1968, vol. one, pp. 418–423).

1.2 Tardily Antiquity

Although Galen was the supreme medical authority until the seventeenth century, his views were oft extended or modified. An early example of this miracle is the addition of a ventricular localization theory of psychological faculties to Galen's account of the brain. The first theory of this type that nosotros know of was presented by Posidonius of Byzantium (end of the fourth century CE), who said that imagination is due to the forepart of the brain, reason to the middle ventricle, and memory to the hind part of the brain (Aetius 1534, 1549, book 6, ch. 2). A few decades afterwards, Nemesius of Emesa (ca. 400 CE) was more than specific and maintained that the anterior ventricle is the organ of imagination, the middle ventricle the organ of reason, and the posterior ventricle the organ of retentiveness (Nemesius 1802, chs. 6–13). The latter theory was nearly universally adopted until the middle of the sixteenth century, although there were numerous variants. The most of import variant was due to Avicenna (980–1037 CE), who devised it by projecting the psychological distinctions plant in Aristotle'south On the soul onto the ventricular system of the brain (Rahman 1952).

1.3 Center Ages

In a treatise called On the difference between spirit and soul, Qusta ibn Luqa (864–923) combined Nemesius' ventricular localization doctrine with Galen's account of a worm-like part of the encephalon that controls the period of animal spirit between the heart and posterior ventricles. He wrote that people who want to remember look up because this raises the worm-like particle, opens the passage, and enables the retrieval of memories from the posterior ventricle. People who want to think, on the other hand, look down because this lowers the particle, closes the passage, and protects the spirit in the middle ventricle from existence disturbed by memories stored in the posterior ventricle (Constantinus Africanus 1536, p. 310).

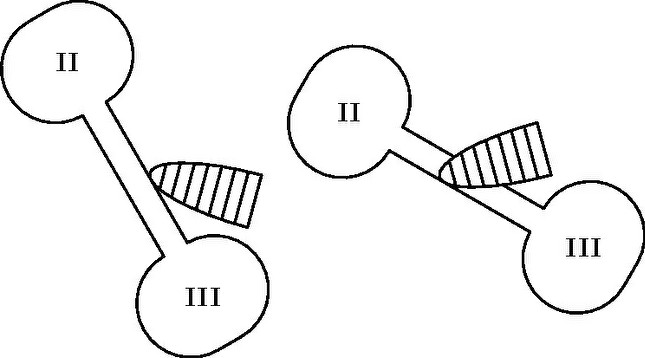

Figure 2. Qusta ibn Luqa'southward Theory (modern schematic reconstruction, view from the left). Thinking is associated with the animal spirit in the middle ventricle (II), memories are stored in the posterior ventricle (Iii). Left: people who want to remember look upwards because this raises the worm-similar obstacle and enables the passage of memories from the posterior to the middle ventricle. Correct: people who desire to think look downwards because this depresses the worm-like obstacle and isolates the heart ventricle from the contents of the posterior ventricle.

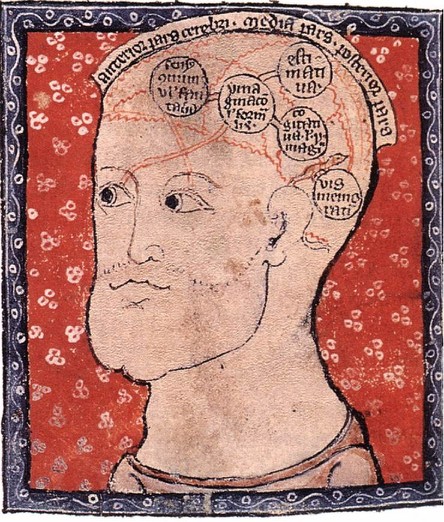

Figure 3. The Worm-Like Obstruction. This illumination from ca. 1300 shows how the worm guards the archway of the posterior ventricle (University Library, Cambridge, ms Gr.one thousand.ane.ane; Source: Web Gallery of Art).

Qusta's treatise was very influential in thirteenth-century scholastic Europe (Wilcox 1985).

In several later on medieval texts, the term pinea was practical to the worm-like obstacle, and so that the view that the pineal gland regulates the flow of spirits (the theory that Galen had rejected) fabricated a come-back (Vincent de Beauvais 1494, fol. 342v; Vincent de Beauvais 1624, col. 1925; Israeli 1515, part two, fol. 172v and fol. 210r; Publicius 1482, ch. Ingenio conferentia). The authors in question seemed ignorant of the stardom that Galen had fabricated between the pineal gland and the worm-like appendage. To add together to the defoliation, Mondino dei Luzzi (1306) described the choroid plexus in the lateral ventricles as a worm which can open and close the passage between the anterior and center ventricles, with the result that, in the belatedly Middle Ages, the term 'worm' could refer to no less than three dissimilar parts of the brain: the vermis of the cerebellum, the pineal body and the choroid plexus.

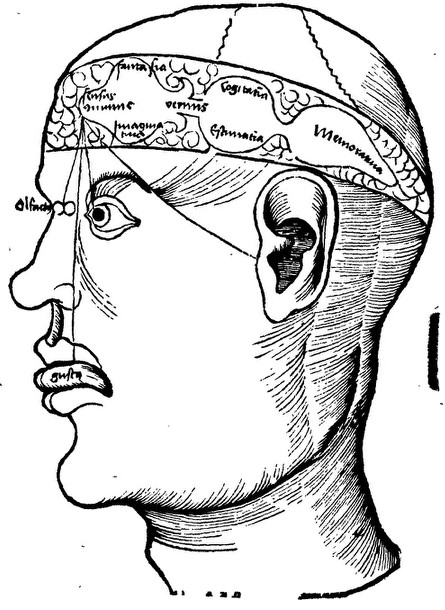

Figure 4. The Worm Co-ordinate to Mondino (view from the left). In this diagram, at that place is a "worm" ("vermis") between the anterior and center ventricles, in conformity with Mondino's Anothomia (Reisch 1535, p. 883).

Figure 5. The Worm According to Mondino (view from above). In this view of the brain from above, the label "worm" ("vermis") is applied to the choroid plexus in the lateral and third ventricles, only as in Mondino'south Anothomia (Berengario da Carpi 1530, fol. O3r).

i.iv Renaissance

In the beginning of the sixteenth century, anatomy fabricated great progress and at least ii developments took identify that are important from our indicate of view. First, Niccolò Massa (1536, ch. 38) discovered that the ventricles are non filled with some blusterous or vaporous spirit just with fluid (the liquor cerebro-spinalis). 2nd, Andreas Vesalius (1543, book 7) rejected all ventricular localization theories and all theories according to which the choroid plexus, pineal gland or vermis of the cerebellum can regulate the flow of spirits in the ventricles of the brain.

ii. Descartes' Views on the Pineal Gland

Today, René Descartes (1596–1650) is mainly known considering of his contributions to mathematics and philosophy. Simply he was highly interested in anatomy and physiology besides. He paid so much attending to these subjects that it has been suggested that "if Descartes were alive today, he would be in accuse of the CAT and PET scan machines in a major research hospital" (Watson 2002, p. 15). Descartes discussed the pineal gland both in his outset volume, the Treatise of man (written earlier 1637, simply only published posthumously, first in an imperfect Latin translation in 1662, and then in the original French in 1664), in a number of messages written in 1640–41, and in his concluding book, The passions of the soul (1649).

2.i The Treatise of Man

In the Treatise of homo, Descartes did not describe human, only a kind of conceptual models of man, namely creatures, created by God, which consist of two ingredients, a trunk and a soul. "These men will be composed, as we are, of a soul and a body. First I must describe the body on its own; then the soul, over again on its own; and finally I must bear witness how these two natures would have to be joined and united in social club to constitute men who resemble us" (AT Xi:119, CSM I:99). Unfortunately, Descartes did not fulfill all of these promises: he discussed merely the trunk and said most zip nigh the soul and its interaction with the body.

The bodies of Descartes' hypothetical men are nothing just machines: "I suppose the body to be nothing only a statue or motorcar made of earth, which God forms with the explicit intention of making it as much equally possible like u.s.a." (AT XI:120, CSM I:99). The working of these bodies can exist explained in purely mechanical terms. Descartes tried to evidence that such a mechanical account tin can include much more than one might expect considering it can provide an explanation of "the digestion of nutrient, the beating of the heart and arteries, the nourishment and growth of the limbs, respiration, waking and sleeping, the reception by the external sense organs of light, sounds, smells, tastes, heat and other such qualities, the imprinting of the ideas of these qualities in the organ of the 'common' sense and the imagination, the retention or stamping of these ideas in the memory, the internal movements of the appetites and passions, and finally the external movements of all the limbs" (AT Eleven:201, CSM I:108). In scholastic philosophy, these activities were explained by referring to the soul, but Descartes proudly pointed out that he did not have to invoke this notion: "it is not necessary to excogitate of this motorcar as having any vegetative or sensitive soul or other principle of movement and life, apart from its blood and its spirits, which are agitated past the oestrus of the fire called-for continuously in its heart—a fire which has the aforementioned nature as all the fires that occur in inanimate bodies" (AT Xi:201, CSM I:108).

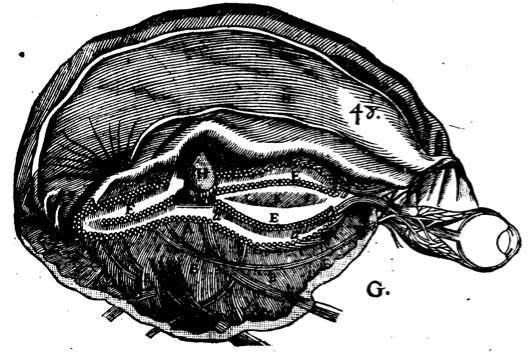

The pineal gland played an important function in Descartes' business relationship considering it was involved in sensation, imagination, memory and the causation of bodily movements. Unfortunately, however, some of Descartes' basic anatomical and physiological assumptions were totally mistaken, not only by our standards, but also in light of what was already known in his time. It is important to keep this in mind, for otherwise his account cannot be understood. First, Descartes idea that the pineal gland is suspended in the center of the ventricles.

Figure half-dozen. The Pineal Gland According to Descartes. This image from the 1664 edition of the Treatise of homo illustrates Descartes' view that the pineal gland (H) is suspended in the middle of the ventricles (Descartes 1664, p. 63).

Merely information technology is not, as Galen had already pointed out (see above). Secondly, Descartes thought that the pineal gland is full of animal spirits, brought to it by many small arteries which surround it. But as Galen had already pointed out, the gland is surrounded by veins rather than arteries. Third, Descartes described these animal spirits as "a very fine current of air, or rather a very lively and pure flame" (AT Xi:129, CSM I:100) and as "a certain very fine air or wind" (AT XI:331, CSM I:330). He idea that they inflate the ventricles just like the sails of a ship are inflated by the wind. Simply every bit we accept mentioned, a century earlier Massa had already discovered that the ventricles are filled with liquid rather than an air-similar substance.

In Descartes' description of the part of the pineal gland, the blueprint in which the fauna spirits flow from the pineal gland was the crucial notion. He explained perception as follows. The nerves are hollow tubes filled with animal spirits. They as well contain certain small fibers or threads which stretch from one terminate to the other. These fibers connect the sense organs with certain small valves in the walls of the ventricles of the brain. When the sensory organs are stimulated, parts of them are ready in motility. These parts then brainstorm to pull on the small fibers in the nerves, with the outcome that the valves with which these fibers are connected are pulled open up, some of the animate being spirits in the pressurized ventricles of the encephalon escape, and (because nature abhors a vacuum) a low-pressure image of the sensory stimulus appears on the surface of the pineal gland. It is this image which then "causes sensory perception" of whiteness, tickling, pain, and then on. "It is not [the figures] imprinted on the external sense organs, or on the internal surface of the brain, which should exist taken to be ideas—simply only those which are traced in the spirits on the surface of the gland H (where the seat of the imagination and the 'mutual' sense is located). That is to say, it is only the latter figures which should be taken to be the forms or images which the rational soul united to this machine will consider directly when information technology imagines some object or perceives it by the senses" (AT XI:176, CSM I:106). Information technology is to be noted that the reference to the rational soul is a chip premature at this stage of Descartes' story because he had announced that he would, to begin with, discuss only the functions of bodies without a soul.

Imagination arises in the same way equally perception, except that information technology is not caused by external objects. Continuing the simply-quoted passage, Descartes wrote: "And note that I say 'imagines or perceives by the senses'. For I wish to utilize the term 'idea' generally to all the impressions which the spirits can receive as they leave gland H. These are to be attributed to the 'common' sense when they depend on the presence of objects; only they may likewise continue from many other causes (as I shall explain after), and they should then be attributed to the imagination" (AT XI:177, CSM I:106). Descartes' materialistic interpretation of the term 'idea' in this context is striking. But this is not the only sense in which he used this term: when he was talking about real men instead of mechanical models of their bodies, he also referred to 'ideas of the pure mind' which exercise not involve the 'corporeal imagination'.

Descartes' mechanical caption of retentiveness was as follows. The pores or gaps lying betwixt the tiny fibers of the substance of the brain may become wider as a event of the menstruation of animal spirits through them. This changes the pattern in which the spirits will afterwards period through the brain and in this way figures may be "preserved in such a way that the ideas which were previously on the gland tin be formed over again long afterwards without requiring the presence of the objects to which they correspond. And this is what retention consists in" (AT Eleven:177, CSM I:107).

Finally, Descartes presented an account of the origin of bodily movements. He idea that there are two types of bodily motility. First, at that place are movements which are acquired by movements of the pineal gland. The pineal gland may be moved in 3 ways: (one) by "the force of the soul," provided that there is a soul in the car; (two) past the spirits randomly swirling almost in the ventricles; and (3) as a result of stimulation of the sense organs. The role of the pineal gland is similar in all 3 cases: equally a result of its movement, it may come shut to some of the valves in the walls of the ventricles. The spirits which continuously menstruum from it may then push these valves open, with the result that some of the beast spirits in the pressurized ventricles can escape through these valves, period to the muscles by means of the hollow, spirit-filled nerves, open or close certain valves in the muscles which control the tension in those muscles, and thus bring about contraction or relaxation of the muscles. As in perception, Descartes applied the term 'thought' again to the period of animal spirits from the pineal gland: "And note that if we accept an idea about moving a member, that idea—consisting of nothing but the way in which spirits flow from the gland—is the cause of the movement itself" (AT Eleven:181; Hall 1972, p. 92). Apart from the just-mentioned blazon of bodily motions, caused by motions of the pineal gland, in that location is also a second kind, namely reflexes. The pineal gland plays no role with respect to them. Reflexes are caused by direct exchanges of animal spirits betwixt channels within the hemispheres of the brain. (Descartes did not know that there are "spinal reflexes".) They practice not necessarily give ascent to ideas (in the sense of currents in the ventricles) and are non brought about by motions of the pineal gland.

two.2 Between the Treatise of Man and The Passions of the Soul

The kickoff remarks most the pineal gland which Descartes published are to exist constitute in his Dioptrics (1637). The fifth discourse of this book contains the thesis that "a certain small gland in the middle of the ventricles" is the seat of the sensus communis, the general kinesthesia of sense (AT Half-dozen:129, not in CSM I). In the sixth discourse, we detect the post-obit interesting observation on visual perception: "At present, when this moving-picture show [originating in the eyes] thus passes to the inside of our caput, it all the same bears some resemblance to the objects from which it gain. As I have amply shown already, however, nosotros must not retrieve that it is by means of this resemblance that the picture show causes our sensory perception of these objects—as if in that location were yet other eyes within our brain with which we could perceive information technology. Instead we must hold that it is the movements composing this picture which, acting straight upon our soul in then far equally it is united to our body, are ordained by nature to make it have such sensations" (AT Six:130, CSM I:167). This remark shows that Descartes tried to avert the and then-called "homuncular fallacy," which explains perception by assuming that there is a picayune man in the head who perceives the output of the sense organs, and obviously leads to an infinite regress.

Descartes' brusk remarks virtually a small gland in the middle of the brain which is of paramount importance apparently generated a lot of interest. In 1640, Descartes wrote several letters to answer a number of questions that various persons had raised. In these letters, he not but identified the small-scale gland as the conarion or pineal gland (29 Jan 1640, AT III:19, CSMK 143), but also added some interesting points to the Treatise of man. Showtime, he explained why he regarded it equally the principal seat of the rational soul (a point that he had non yet addressed in the Treatise of man): "My view is that this gland is the master seat of the soul, and the place in which all our thoughts are formed. The reason I believe this is that I cannot find whatever part of the brain, except this, which is not double. Since we come across only 1 affair with two eyes, and hear just one vocalization with ii ears, and in short have never more than 1 thought at a time, it must necessarily be the case that the impressions which enter by the two eyes or by the two ears, and so on, unite with each other in some function of the trunk before being considered past the soul. Now information technology is impossible to find any such identify in the whole head except this gland; moreover it is situated in the most suitable possible place for this purpose, in the middle of all the concavities; and information technology is supported and surrounded by the trivial branches of the carotid arteries which bring the spirits into the encephalon" (29 January 1640, AT 3:19–20, CSMK 143). And as he wrote later that year: "Since it is the only solid function in the whole brain which is single, it must necessarily be the seat of the common sense, i.e., of thought, and consequently of the soul; for one cannot be separated from the other. The only alternative is to say that the soul is non joined immediately to any solid part of the torso, but only to the beast spirits which are in its concavities, and which enter it and get out it continually like the water of river. That would certainly be thought as well absurd" (24 December 1640, AT 3:264, CSMK 162). Another important property of the pineal gland, in Descartes' eyes, is that it is small, light and hands movable (29 January 1640, AT Three:20, CSMK 143). The pituitary gland is, though small, undivided and located in the midline, not the seat of the soul because information technology is outside the brain and entirely immobile (24 Dec 1640, AT III:263, CSMK 162). The processus vermiformis of the cerebellum (equally Descartes called the appendage which Galen had discussed) is not a suitable candidate considering it is divisible into ii halves (30 July 1640, AT Iii:124, not in CSMK).

A second interesting addition to the Treatise of man that Descartes made in these messages concerns memory. Descartes at present wrote that memories may not but be stored in the hemispheres, but also in the pineal gland and in the muscles (29 January 1640, AT Iii:xx, CSMK 143; 1 Apr 1640, AT Iii:48, CSMK 146). Autonomously from this, there is also another kind of memory, "entirely intellectual, which depends on the soul alone" (1 April 1640, AT III:48, CSMK 146).

Descartes' thesis that "the pineal gland is the seat of the sensus communis" was soon dedicated by others. The medical student Jean Cousin defended it in Paris in January 1641 (Cousin 1641) and the professor of theoretical medicine Regius defended information technology in Utrecht in June 1641 (Regius 1641, third disputation). Mersenne described the reaction of Cousin's audience in a letter to Descartes, simply this letter never reached its destination and is now lost (Lokhorst and Kaitaro 2001).

2.3 The Passions of the Soul

The nigh all-encompassing account of Descartes' pineal neurophysiology and pineal neuropsychology is to exist found in his The passions of the soul (1649), the last book that he published.

The Passions may be seen as a continuation of the Treatise of human being, except that the management of approach is different. The Treatise of man starts with the body and announces that the soul volition be treated later on. The determination would probably take been that we are duplicate from the hypothetical "men who resemble u.s." with which the Treatise of man is concerned and that we are merely such machines equipped with a rational soul ourselves. In the Passions, Descartes starts from the other finish, with man, and begins by splitting man up into a body and a soul.

Descartes' benchmark for determining whether a function belongs to the body or soul was as follows: "annihilation we experience as being in u.s.a., and which nosotros see tin can also exist in wholly inanimate bodies, must exist attributed only to our trunk. On the other hand, anything in united states which we cannot conceive in any manner as capable of belonging to a body must exist attributed to our soul. Thus, because we accept no conception of the body every bit thinking in any way at all, we have reason to believe that every kind of idea present in us belongs to the soul. And since we practice not uncertainty that there are inanimate bodies which tin movement in as many different ways as our bodies, if non more than, and which have as much estrus or more […], we must believe that all the estrus and all the movements nowadays in us, in so far as they do not depend on thought, belong solely to the trunk" (AT Xi:329, CSM I:329).

Just before he mentioned the pineal gland for the first time, Descartes emphasized that the soul is joined to the whole body: "We demand to recognize that the soul is really joined to the whole body, and that we cannot properly say that it exists in any 1 role of the body to the exclusion of the others. For the body is a unity which is in a sense indivisible because of the organisation of its organs, these being so related to one another that the removal of any one of them renders the whole body defective. And the soul is of such a nature that it has no relation to extension, or to the dimensions or other backdrop of the matter of which the body is composed: it is related solely to the whole assemblage of the body'south organs. This is obvious from our inability to conceive of a half or a 3rd of a soul, or of the extension which a soul occupies. Nor does the soul become any smaller if nosotros cut off some part of the torso, only information technology becomes completely carve up from the trunk when nosotros suspension up the assemblage of the body's organs" (AT Eleven:351, CSM I:339). Only even though the soul is joined to the whole body, "nevertheless there is a certain role of the body where it exercises its functions more particularly than in all the others. […] The part of the body in which the soul straight exercises its functions is not the heart at all, or the whole of the brain. It is rather the innermost part of the encephalon, which is a sure very minor gland situated in the centre of the brain's substance and suspended above the passage through which the spirits in the encephalon's anterior cavities communicate with those in its posterior cavities. The slightest movements on the function of this gland may alter very greatly the class of these spirits, and conversely any modify, even so slight, taking place in the class of the spirits may do much to modify the movements of the gland" (AT XI:351, CSM I:340).

The view that the soul is attached to the whole body is already plant in St Augustine's works: "in each body the whole soul is in the whole body, and whole in each part of it" (On the Trinity, book 6, ch. vi). St Thomas Aquinas accustomed this view and explained information technology by proverb that the soul is completely present in each part of the body just equally whiteness is, in a certain sense, completely present in each role of the surface of a bare sheet of paper. In deference to Aristotle, he added that this does not exclude that some organs (the eye, for example) are more important with respect to some of the faculties of the soul than others are (Summa theologica, part 1, question 76, art. 8; Quaestiones disputatae de anima, fine art. 10; Summa contra gentiles, volume 2, ch. 72).

Augustine's and Aquinas' thesis sounds reasonable as long every bit the soul is regarded as the principle of life. The principle of life may well held to be completely present in each living part of the body (but every bit biologists nowadays say that the complete genome is present in each living cell). However, Descartes did not regard the soul as the principle of life. He regarded information technology as the principle of thought. This makes 1 wonder what he may have meant by his remark. What would a principle of thought be doing in the bones and toes? One might recollect that Descartes meant that, although the pineal gland is the only organ to which the soul is immediately joined, the soul is nevertheless indirectly joined to the rest of the body past means of the threads and spirits in the nerves. Merely Descartes did not view this every bit firsthand attachment: "I do not remember that the soul is and so imprisoned in the gland that information technology cannot act elsewhere. But utilizing a thing is not the same as being immediately joined or united to it" (30 July 1640). Moreover, it is clear that not all parts of the torso are innervated.

The solution of this puzzle is to be establish in a passage which Descartes wrote a few years before the Passions, in which he compared the listen with the heaviness or gravity of a trunk: "I saw that the gravity, while remaining coextensive with the heavy body, could exercise all its strength in any one function of the body; for if the trunk were hung from a rope attached to whatsoever office of it, it would still pull the rope down with all its forcefulness, just as if all the gravity existed in the part really touching the rope instead of being scattered through the remaining parts. This is exactly the way in which I now understand the heed to be coextensive with the trunk—the whole listen in the whole body and the whole heed in any i of its parts" (Replies to the sixth prepare of objections to the Meditations, 1641, AT 7:441, CSM Ii:297). He added that he thought that our ideas about gravity are derived from our conception of the soul.

In the secondary literature one oftentimes meets the merits that Descartes maintained that the soul has no spatial extension, just this claim is obviously wrong in view of Descartes' own assertions. Those who make information technology may have been misled by Descartes' quite dissimilar merits that extension is non the principal attribute of the soul, where 'master' has a conceptual or epistemic sense.

Most of the themes discussed in the Treatise of man and in the correspondence of 1640 (quoted above) reappear in the Passions of the soul, as this summary indicates: "the small gland which is the chief seat of the soul is suspended within the cavities containing these spirits, then that information technology tin can be moved by them in as many different ways as there are perceptible differences in the objects. Just it can as well be moved in various dissimilar ways past the soul, whose nature is such that it receives as many different impressions—that is, it has as many different perceptions every bit there occur different movements in this gland. And conversely, the mechanism of our body is so synthetic that simply past this gland's being moved in whatsoever way by the soul or by any other crusade, it drives the surrounding spirits towards the pores of the brain, which directly them through the nerves to the muscles; and in this manner the gland makes the spirits move the limbs" (AT XI:354, CSM I:341).

The clarification of recollection is more bright than in the Treatise of human being: "Thus, when the soul wants to remember something, this volition makes the gland lean first to one side and so to some other, thus driving the spirits towards dissimilar regions of the brain until they come upon the 1 containing traces left by the object we want to remember. These traces consist simply in the fact that the pores of the brain through which the spirits previously made their way owing to the presence of this object accept thereby become more apt than the others to exist opened in the same way when the spirits once more period towards them. And then the spirits enter into these pores more easily when they come up upon them, thereby producing in the gland that special movement which represents the same object to the soul, and makes it recognize the object every bit the i it wanted to remember" (AT 11:360, CSM I:343).

The clarification of the issue of the soul on the torso in the causation of bodily movement is also more than detailed: "And the activity of the soul consists entirely in the fact that but by willing something information technology brings it near that the niggling gland to which it is closely joined moves in the manner required to produce the effect corresponding to this volition" (AT XI:359, CSM I:343).

The pineal neurophysiology of the passions or emotions is similar to what is occurring in perception: "the ultimate and most proximate cause of the passions of the soul is simply the agitation by which the spirits move the little gland in the middle of the brain" (AT 11:371, CSM I:349). However, there are some new ingredients which have no parallel in the Treatise of man. For example, in a chapter on the "conflicts that are usually supposed to occur between the lower role and the higher part of the soul," we read that "the lilliputian gland in the middle of the brain can be pushed to one side past the soul and to the other side by the animal spirits" and that conflicting volitions may outcome in a conflict between "the force with which the spirits push button the gland so as to cause the soul to desire something, and the force with which the soul, by its volition to avoid this thing, pushes the gland in a contrary direction" (AT 11:364, CSM I:345).

In later times, it was often objected that incorporeal volitions cannot move the corporeal pineal gland because this would violate the law of the conservation of energy. Descartes did not take this problem considering he did not know this law. He may nevertheless have foreseen difficulties because, when he stated his third law of motion, he left the possibility open that it does not apply in this case: "All the particular causes of the changes which bodies undergo are covered by this third law—or at least the law covers all changes which are themselves corporeal. I am not here inquiring into the beingness or nature of any power to motility bodies which may be possessed by human minds, or the minds of angels" (AT 8:65, CSM I:242).

2.4 Body and Soul

1 would similar to know a little more about the nature of the soul and its relationship with the body, but Descartes never proposed a last theory most these issues. From passages such as the ones we have just quoted one might infer that he was an interactionist who thought that there are causal interactions between events in the body and events in the soul, but this is by no means the merely estimation that has been put forrard. In the secondary literature, one finds at least the post-obit interpretations.

- Descartes was a Scholastic-Aristotelian hylomorphist, who idea that the soul is non a substance but the first authenticity or substantial form of the living body (Hoffman 1986, Skirry 2003).

- He was a Platonist who became more than and more farthermost: "The get-go stage in Descartes' writing presents a moderate Platonism; the 2nd, a scholastic Platonism; the third, an extreme Platonism, which, post-obit Maritain, we may also phone call angelism: 'Cartesian dualism breaks human up into two complete substances, joined to another no one knows how: 1 the i hand, the trunk which is only geometric extension; on the other, the soul which is only thought—an affections inhabiting a automobile and directing it by means of the pineal gland' (Maritain 1944, p. 179). Not that there is anything very 'moderate' well-nigh his original position—it is simply the surprising terminal position that can justify assigning it that championship" (Voss 1994, p. 274).

- He articulated—or came shut to articulating—a trialistic distinction between 3 archaic categories or notions: extension (body), thought (mind) and the union of body and listen (Cottingham 1985; Cottingham 1986, ch. 5).

- He was a dualistic interactionist, who thought that the rational soul and the body have a causal influence on each other. This is the interpretation one finds in most undergraduate textbooks (east.g., Copleston 1963, ch. iv).

- He was a dualist who denied that causal interactions between the body and the mind are possible and therefore defended "a parallelism in which changes of definite kinds occurrent in the nerves and brains synchronize with sure mental states correlated with them" (Keeling 1963, p. 285).

- He was, at to the lowest degree to a sure extent, a not-parallelist because he believed that pure actions of the soul, such as doubting, understanding, affirming, denying and willing, tin occur without whatsoever respective or correlated physiological events taking place (Wilson 1978, p. 80; Cottingham 1986, p. 124). "The brain cannot in whatever way be employed in pure agreement, but only in imagining or perceiving by the senses" (AT VII:358, CSM 2:248).

- He was a dualistic occasionalist, but similar his early followers Cordemoy (1666) and La Forge (1666), and thought that mental and concrete events are nothing merely occasions for God to human action and bring nearly an result in the other domain (Hamilton in Reid 1895, vol. two, p. 961 n).

- He was an epiphenomenalist as far equally the passions are concerned: he viewed them every bit causally ineffectual by-products of brain activity (Lyons 1980, pp. iv–5).

- He was a supervenientist in the sense that he thought that the will is supervenient to (determined by) the body (Clarke 2003, p. 157).

- The neurophysiology of the Treatise of man "seems fully consistent […] with a materialistic dual-attribute identity theory of mind and body" (Smith 1998, p. seventy).

- He was a skeptical idealist (Kant 1787, p. 274).

- He was a covert materialist who hid his truthful opinion out of fear of the theologians (La Mettrie 1748).

At that place seem to be merely ii well-known theories from the history of the philosophy of mind that have not been attributed to him, namely behaviorism and functionalism. Merely even hither 1 could make a case. According to Hoffman (1986) and Skirry (2003), Descartes accepted Aristotle's theory that the soul is the form of the body. Co-ordinate to Kneale (1963, p. 839), the latter theory was "a sort of behaviourism". Co-ordinate to Putnam (1975), Nussbaum (1978) and Wilkes (1978), information technology was similar to gimmicky functionalism. By transitivity, one might conclude that Descartes was either a sort of behavorist or a functionalist.

Each of these interpretations agrees with at to the lowest degree some passages in Descartes' writings, but none agrees with all of them. Taken together, they suggest that Descartes' philosophy of mind contains echoes of all theories that had been proposed earlier him and anticipations of all theories that were adult afterwards: it is a multi-faceted diamond in which all mind-body theories that have ever been proposed are reflected.

In his later years, Descartes was well aware that he had not successfully finished the project that he had begun in the Treatise of man and had not been able to codify one comprehensive mind-body theory. He sometimes expressed irritation when others reminded him of this. In reply to the questions "how can the soul move the trunk if information technology is in no way fabric, and how can it receive the forms of corporeal objects?" he said that "the most ignorant people could, in a quarter of an hour, enhance more questions of this kind than the wisest men could deal with in a lifetime; and this is why I take not bothered to answer any of them. These questions presuppose amongst other things an explanation of the union between the soul and the body, which I take not yet dealt with at all" (12 January 1646, AT IX:213, CSM II:275). On other occasions, he came close to admitting defeat. "The soul is conceived merely past the pure intellect; body (i.due east. extension, shapes and motions) tin can as well be known by the intellect alone, just much better past the intellect aided by the imagination; and finally what belongs to the union of the soul and the body is known only obscurely by the intellect lone or even by the intellect aided past the imagination, merely it is known very clearly by the senses. […] Information technology does not seem to me that the human listen is capable of forming a very distinct conception of both the stardom between the soul and the body and their matrimony; for to do this information technology is necessary to conceive them as a unmarried thing and at the same fourth dimension to conceive them as two things; and this is absurd" (28 June 1643, AT 3:693, CSMK 227). He admitted that the unsuccessfulness of his enterprise might take been his own error because he had never spent "more than a few hours a solar day in the thoughts which occupy the imagination and a few hours a yr on those which occupy the intellect alone" (AT III:692, CSMK 227). But he had done so for a practiced reason because he thought it "very harmful to occupy one'southward intellect frequently upon meditating upon [the principles of metaphysics which give us or knowledge of God and our soul], since this would impede it from devoting itself to the functions of the imagination and the senses" (AT Iii:695, CSMK 228). He advised others to do besides: "ane should not devote so much effort to the Meditations and to metaphysical questions, or give them elaborate handling in commentaries and the like. […] They depict the mind also far abroad from physical and observable things, and go far unfit to study them. Notwithstanding it is but these physical studies that are most desirable for people to pursue, since they would yield abundant benefits for life" (Conversation with Burman, 1648, AT Five:165, CSMK 346–347). We will follow this wise advice.

3. Post-Cartesian Development

3.1 Reactions to Descartes' Views

Only a few people accepted Descartes' pineal neurophysiology when he was notwithstanding alive, and it was near universally rejected after his expiry. Willis wrote about the pineal gland that "we can scarce believe this to be the seat of the Soul, or its main Faculties to arise from it; because Animals, which seem to be nigh quite destitute of Imagination, Memory, and other superior Powers of the Soul, accept this Glandula or Kernel large and off-white plenty" (Willis 1664, ch. 14, as translated in Willis 1681). Steensen (1669) pointed out that Descartes' basic anatomical assumptions were wrong considering the pineal gland is not suspended in the middle of the ventricles and is not surrounded by arteries but veins. He argued that we know next to nada about the brain. Camper (1784) seems to have been the very last 1 to uphold the Cartesian thesis that the pineal gland is the seat of the soul, although one may wonder whether he was completely serious. In philosophy, a position chosen "Cartesian interactionism" immediately provoked "either ridicule or disgust" (Spinoza 1677, part iv, preface), usually because it was seen as raising more than issues than it solved, and information technology continues to practice so to this day, but as we take already indicated, it is doubtful whether Descartes was a Cartesian interactionist himself.

Some of the reasons that Descartes gave for his view that the pineal gland is the chief seat of the soul died out more than slowly than this view itself. For case, his argument that "since our soul is not double, but one and indivisible, […] the role of the body to which it is most immediately joined should also be unmarried and non divided into a pair of similar parts" (xxx July 1640, AT Three:124, CSMK 149), for instance, withal played a part when Lancisi (1712) identified the unpaired corpus callosum in the midline of the brain equally the seat of the soul. This view was, still, refuted by Zinn (1749) in a serial of split-brain experiments on dogs. Lamettrie and many others explicitly rejected the thesis that the unity of experience requires a respective unity of the seat of the soul (Lamettrie 1745, ch. x).

3.2 Scientific Developments

In scientific studies of the pineal gland, trivial progress was made until the 2nd one-half of the nineteenth century. As late as 1828, Magendie could still advance the theory that Galen had dismissed and Qusta ibn Luca had embraced: he suggested that it is "a valve designed to open and shut the cognitive aqueduct" (Magendie 1828). Towards the stop of the nineteenth century, withal, the state of affairs started to change (Zrenner 1985). Beginning, several scientists independently launched the hypothesis that the pineal gland is a phylogenic relic, a vestige of a dorsal third centre. A modified form of this theory is still accepted today. 2nd, scientists began to surmise that the pineal gland is an endocrine organ. This hypothesis was fully established in the twentieth century. The hormone secreted past the pineal gland, melatonin, was first isolated in 1958. Melatonin is secreted in a circadian rhythm, which is interesting in view of the hypothesis that the pineal gland is a vestigial third heart. Melatonin was hailed every bit a "wonder drug" in the 1990s and then became one of the best-sold wellness supplements. The history of pineal gland research in the twentieth century has received some attention from philosophers of science (Immature 1973, McMullen 1979), but this was only a curt-lived give-and-take.

three.3 Pseudo-Scientific discipline

Equally philosophy reduced the pineal gland to just another office of the brain and science studied information technology as one endocrine gland amongst many, the pineal gland continued to have an exalted status in the realm of pseudo-science. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, Madame Blavatsky, the founder of theosophy, identified the "3rd centre" discovered past the comparative anatomists of her time with the "center of Shiva" of "the Hindu mystics" and ended that the pineal trunk of modern human being is an atrophied vestige of this "organ of spiritual vision" (Blavatsky 1888, vol. 2, pp. 289–306). This theory is however fairly well-known today.

3.four Conclusion

Descartes was neither the first nor the last philosopher who wrote near the pineal gland, but he attached more than importance to information technology than any other philosopher did. Descartes tried to explain virtually of our mental life in terms of processes involving the pineal gland, merely the details remained unclear, even in his own optics, and his enterprise was soon abased for both philosophical and scientific reasons. Even so, the pineal gland remains intriguing in its own right and is still intensely studied today, with even a whole journal defended to it, the Periodical of Pineal Research.

How Did Descartes Explain How The Brain Controlled Movement?,

Source: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/pineal-gland/

Posted by: molinarotapeon58.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Did Descartes Explain How The Brain Controlled Movement?"

Post a Comment